Basic electronic components: Difference between revisions

m (→Capacitors) |

|||

| Line 80: | Line 80: | ||

A failing electrolytic capacitor can often be recognised as a build up of internal pressure may cause the top to bulge, or the capacitor no longer to sit flush with the board, or electrolyte to leak from the bottom. At this stage it probably won't be performing well, causing the equipment to malfunction. If not replaced, it may even explode. However the fact that an electrolytic capacitor shows no visible sign of deterioration is by no means a reliable indicator that it's good. | A failing electrolytic capacitor can often be recognised as a build up of internal pressure may cause the top to bulge, or the capacitor no longer to sit flush with the board, or electrolyte to leak from the bottom. At this stage it probably won't be performing well, causing the equipment to malfunction. If not replaced, it may even explode. However the fact that an electrolytic capacitor shows no visible sign of deterioration is by no means a reliable indicator that it's good. | ||

The simplest reliable method of testing an electrolytic capacitor is with an ESR (Equivalent Series Resistance) tester. A basic one with a graphical display but without a case is available very cheaply from Far Eastern sellers. This is an excellent investment as it will also identify and test many other types of component. A good electrolytic capacitor should show an ESR of a fraction of an ohm, and a vloss (another measure given by these testers) of a fraction of a percent. | |||

If an electrolytic capacitor has to be replaced it's very important to fit the replacement the right way round (the "+" or the "-" marking on the same side) as otherwise the electrolytic forming process will be reversed and it will very rapidly fail. | If an electrolytic capacitor has to be replaced it's very important to fit the replacement the right way round (the "+" or the "-" marking on the same side) as otherwise the electrolytic forming process will be reversed and it will very rapidly fail. | ||

Revision as of 19:59, 6 September 2018

This page covers the basic electronic components: resistors, capacitors and inductors.

Summary

This page covers the basic electronic circuit elements: resistors, capacitors, inductors and transformers - how to identify them, what they do, how they fail and how to test them.

You can read this page on its own if you like, but if you're not already familiar with basic electrical and electronic theory you my find you get more out of it if you first read Electric circuits, volts amps watts and ohms.

Resistors

In many circuits, resistors are the commonest components. They are also generally the cheapest. Their purpose is to resist the flow of electricity, either to limit the current for a given applied voltage (electrical pressure), or to allow a certain voltage (pressure) to build up when a given current flows. Most consist of a thin film of oxide or carbon deposited on a ceramic base. Heat is always generated in a resistor as the current flows, often only a tiny amount but sometimes it can be quite large.

Occasionally you might come across a thermistor, which is a resistor whose resistance decreases markedly with increasing temperature, or a light-dependant resistor (LDR) whose resistance decreases with increasing light levels.

Resistance is measured in Ohms (Ω), kilOhms (kΩ - thousands of Ohms), or megOhms (MΩ - millions of Ohms).

As an interesting aside, whilst resistors may be the commonest and cheapest components in a conventional circuit, they are expensive to fabricate on a silicon chip as they take up a lot of space. Consequently, a chip may contain billions of transistors but few if any resistors at all!

Identification

Resistors have 2 leads and very commonly their resistance is denoted by a number of coloured bands (see resistor colour code).

Surface mount resistors are usually black, rectangular, and with a silvery solder pad on each end. They range in size from a few millimetres down to a fraction of a millimetre.

A power resistor is larger than a regular one allowing it to dissipate the required amount of heat. Often, its value will be printed on it instead of being colour coded.

Fault-finding and Repair

Resistors are usually very reliable. When they fail, generally through overheating, it's almost always as a result of some other component failing and causing too much current to flow. In poorly designed equipment having inadequate provision for heat to escape, moderate overheating over a long period of time may cause a failure.

Potentiometers

A potentiometer (or pot, for short) is simply a resistor with a 3rd connection that can be moved to any point along its length, so as to tap off any desired portion of the total resistance.

Identification

Potentiometers are very commonly used for the volume control in audio equipment (though being superseded by digital controls). These have a spindle with a front panel knob attached, or sometimes a knurled wheel with the edge exposed for adjustment. Twin-gang potentiometers consisting of two mounted on one spindle are often found in stereo equipment for controlling the volume of both stereo channels.

Small potentiometers with a slotted screw head are often found inside equipment for one-time adjustment during manufacture and testing.

Fault-finding and Repair

Potentiometers are much less reliable than fixed resistors. The track can get worn out or crack, or the pressure of the slider on the track can weaken. Sometimes the pressure can be increased by bending the metal slider, though pots are not normally designed to be taken apart and are usually best replaced for a lasting fix.

A quick fix which sometimes works is to squirt switch cleaning fluid into the casing through any gaps or slots you can see, such as beneath the terminals, then repeatedly turn the knob from one end of its travel to the other.

If you find a slotted screw head pot inside a piece of equipment, never adjust it unless you know what it's for and how to find the correct position. Even then, it's worth marking the original position before starting so you can always return to it.

Capacitors

Hopefully you will recall that since like charges repel, electricity hates piling up and as a consequence a circuit must be completed (for example by closing a switch) before a current can flow.

However, electricity will pile up to a limited extent if you apply a voltage (an electrical pressure), but only until the back-pressure equals the voltage you apply.

If there is nowhere much for the electricity to go, that will be very soon, like if you tried to send lots of cars down a short cul-de-sac. But you can make life easier for the electricity if you give it room to spread out, like if there were a large car park at the end of the cul-de-sac. And when you stop pushing the electricity in, it'll all come piling out again as soon as the pressure is released.

A capacitor is a device which allows electricity to pile up by providing space for it to spread out. One of the simplest types just consists of two long strips of aluminium foil separated by a thin insulating strip of plastic, and then rolled up, with a wire connected to each strip. If you connect it to the two terminals of a battery, positive charge will flow out of the positive terminal of the battery and onto one of the strips. Since it's in close proximity to the other strip, it repels an equal amount of positive charge from that strip, which flows back into the negative terminal of the battery. If you disconnect the battery, the electrical charge remains until you connect the two wires together, allowing it to discharge.

A car park has a capacity, but a capacitor has a capacitance. It's measured in Farads (F), or more usually microFarads (μF - millionths of a Farad), nanoFarads (nF - billionths of a Farad), or picoFarads (pF - million-millionths of a Farad).

You can double the capacitance by doubling the surface area that the charge has to spread out in. But you can also do so by halving the thickness of the insulating layer, as this allows the charge on one side to more easily push charge out of the other. But a large enough voltage would destructively break through a very thin insulating layer. A capacitor therefore also has a voltage rating, being the highest voltage that it can safely withstand. This must on no account be exceeded.

Capacitors are used whenever the circuit designer needs to smooth out fluctuations, or when it is required to allow fluctuations (e.g. an audio signal) to flow from one part of a circuit to another whilst blocking any net flow.

Identification

Like resistors, capacitors have just two connections, but they come in a wide range of shapes and sizes. They usually have their capacitance and voltage rating printed on them, and for some types, a maximum temperature.

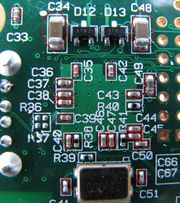

Low value surface mount capacitors are usually grey or buff in colour, rectangular, and with a silvery solder pad on each end. They are typically a few millimetres in length.

Electrolytic capacitors are very frequently used where a high value of capacitance is required. Much the most common are aluminium types, which can be recognised by the cylindrical aluminium case, usually with a plastic film cover. One lead is marked negative ("-") on the adjacent side or end of the case.

Tantalum capacitors are a higher quality (and more expensive) type of electrolytic capacitor using tantalum instead of aluminium. They come as a resin coated bead. Usually, the positive lead is marked "+".

Capacitors connected directly to the mains require a special safety rating. This is Class X for those connected across the mains supply, where a failure could present a fire hazard, and Class Y for those connected between the mains and ground, where the failure could result in an electric shock hazard. Such capacitors must always be replaced with ones of the same class and at least the same voltage rating.

Fault-finding and Repair

Capacitors are usually very reliable except for electrolytic types, which are one of the commonest causes of failure in electronic equipment.

In an electrolytic capacitor, the insulating layer consists of an electrochemically formed film of aluminium oxide with a thickness of only a matter of millionths of a millimetre. This can deteriorate after a long period of disuse (many years) or a shorter period close to or beyond its maximum voltage and/or temperature rating. Also, the liquid used to form the insulating layer can dry out. Poor quality electrolytic capacitors are quite often seen which have failed within their ratings.

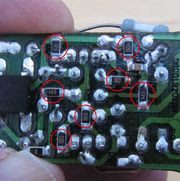

A failing electrolytic capacitor can often be recognised as a build up of internal pressure may cause the top to bulge, or the capacitor no longer to sit flush with the board, or electrolyte to leak from the bottom. At this stage it probably won't be performing well, causing the equipment to malfunction. If not replaced, it may even explode. However the fact that an electrolytic capacitor shows no visible sign of deterioration is by no means a reliable indicator that it's good.

The simplest reliable method of testing an electrolytic capacitor is with an ESR (Equivalent Series Resistance) tester. A basic one with a graphical display but without a case is available very cheaply from Far Eastern sellers. This is an excellent investment as it will also identify and test many other types of component. A good electrolytic capacitor should show an ESR of a fraction of an ohm, and a vloss (another measure given by these testers) of a fraction of a percent.

If an electrolytic capacitor has to be replaced it's very important to fit the replacement the right way round (the "+" or the "-" marking on the same side) as otherwise the electrolytic forming process will be reversed and it will very rapidly fail.

Also, it's always a good idea to replace it with one with a higher voltage and/or temperature rating as the original may have been under-rated. Never ever use a lower rated replacement. If a replacement with the same capacity is not available, a higher value up to twice the original will almost invariably work well, or possibly even better, as there is in any case considerable variation in the capacitance of identically marked electrolytic capacitors.

The site badcaps.net has useful tips on replacing electrolytic capacitors.

Inductors

An inductor simply consists of a coil of wire. When a current flows it creates a magnetic field, which stores energy. By winding it around a magnetic material such as iron or ferrite this gets magnetised, greatly increasing the amount of stored energy.

Whereas a capacitor stores energy in as electrical charge and can be used to smooth out variations in voltage, an inductor stores energy as magnetic flux and tends to smooth out variations in current flow. In fact, there is a beautiful symmetry between the mathematical equations describing capacitors and inductors.

If you combine an inductor and a capacitor in a circuit, the mathematical symmetry blossoms and something rather special happens. A voltage on the capacitor tries to drive a current through the inductor, but once the current gets going the inductor tries to keep it going, and ends up driving the charge onto the other side of the capacitor. So it flows backwards and forwards at a very regular rate, exactly like a child swinging back and forth on a swing. By using a variable capacitor (or a variable inductor), the rate can be altered. This is how nearly all older AM and FM radios tune in the station you want.

Inductance is measured in Henrys (H), milliHenrys (mH - thousandths of a Henry), or microHenrys (μH - millionths of a Henry).

Identification

The smallest value inductors consist of no more than a coil of thick wire standing up from the circuit board. Some small inductors consist of a toroid of ferrite with the coil of wire wound around it, and are easily spotted. In others, the coil is would around a ferrite core shaped like a cotton reel, which may be fitted snugly inside a hollow cylinder of ferrite. For large values of inductance a laminated iron core is used, but this is rarely seen in reasonably modern equipment.

An inductor frequently has no markings on it.

Fault-finding and Repair

There is very little to go wrong in an inductor apart from possibly a badly soldered joint. A very heavy current could cause an inductor to overheat or burn out, but probably not before much damage had been done elsewhere in the circuit.

Transformers

A transformer is simply an inductor with two (or more) coils of wire.

An electric current always creates a magnetic field which loops around the current, and a change in the magnetism looping through a circuit generates a voltage in that circuit. So in a transformer, we apply power to one coil of wire, the primary, and the magnetic flux which this creates induces a voltage in the other coil(s), the secondary(s). But it only works while the magnetic field is changing, and so a transformer can only be used for AC, not DC.

Transformers are very useful for two reasons:

- If the secondary coil has more or fewer turns than the primary, the voltage induced in it will be greater or less than that applied to the primary, in proportion.

- Since the only connection between the primary and the secondary is magnetic, they are electrically isolated from each other. This can be useful for safety reasons, or where the circuit designer needs to block a net flow of current from one part to another.

Identification

If you know how to identify an inductor, then a transformer looks exactly the same except that it has at least 3 wires coming out of it, and nearly always 4 or more.

Older mains powered electronic equipment almost always contains an iron cored mains transformer, which is easy to spot. Good quality audio equipment sometimes uses a toroidal mains transformer as this type produces less stray magnetic field and hence less background hum in the audio output. Newer equipment tends to use a much smaller transformer with a ferrite core.

Fault-finding and Repair

Mains transformers may be required to handle a substantial amount of power, and so in fault conditions they can become very hot. If this results in a breakdown of the insulation between two adjacent turns of either the primary or the secondary, these turns will act like a short-circuited secondary and become very hot indeed.

Rewinding a burnt out mains transformer is not difficult, but rarely would be worth the considerable time and patience required.

And now ...

... you might like to continue by reading about Active components.